The Specialist: Angie Payne on Pressure, Performance, and Possibilities.

Ready.

I've known Angie Payne for a long time... since I was a bolt-hating traddie and she had already decided she was a boulderer. She used to ask when I was going to go bouldering with them, and I'd answer by asking when she'd come plug gear with us. Angie soon moved to Boulder, Colorado, became a superstar, and I left climbing for the hiphop world. When climbing came calling again I soon reconnected with Angie, at a time when she was suffering from an injury, her personal life was enduring turmoil, and her climbing star was dimming.

In a song for Dead Point Magazine, I said this line: "Angie Payne's gon' come back like P-Rob did."

Not long after, in hushed tones as if it were to be kept secret, Angie told me, "I think I'm stronger than ever!"

And so it was.

Oftentimes when people's lives are in the midst of drastic changes, their climbing suffers. Your life was changing direction significantly when you "reemerged" as a bigger, badder, stronger Angie. Can you point to any 2 or 3 things as being the most important catalysts for the refocusing?

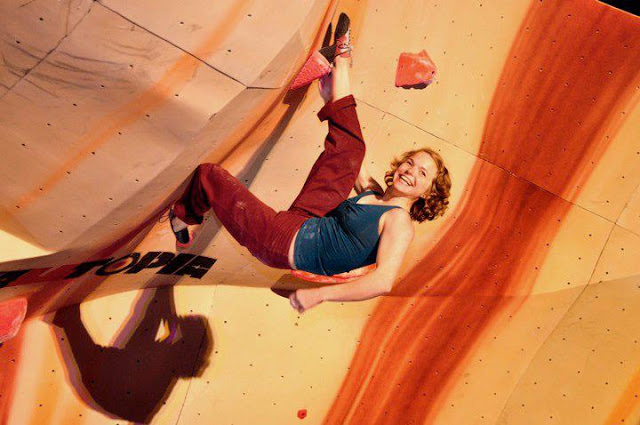

Try Hard. Photo: Gabe Dewitt for the Unified Bouldering Championships

(Angie) I guess the main catalyst for my eventual refocusing actually came more than a year before I really 'reemerged.' In early 2009, I fell in the gym and hurt my ankle badly. In the same week, I also ended a 5-year relationship. It was a rough time in my life, to say the least. After months of supposed 'healing,' I ended up getting surgery, which put me out for another 4 months. All told, I was basically without climbing for 8 months. While I was optimistic that climbing would still be a part of my life, I had sort of resigned myself to the fact that maybe my strongest days were behind me. So when I started climbing again, I didn’t have many expectations for myself -- I was just happy to be moving again. I climbed with more purpose, maybe because I felt an urgency to climb while I was healthy. At the same time, I felt calmer, felt a certain sense of relief, because I felt that I had 'reclaimed' climbing as my own thing in a way. I had been climbing since I was 11 and had definitely gone through phases when I felt that climbing wasn’t really just something I did for myself. There were times when I wondered if I climbed just because I was good at it, or because it was what me and my boyfriend did together, or because I was consumed by the obsession of it. When I came back from my injury, I was horribly out of shape, so I wasn’t particularly “good” at climbing at that time, and I had broken up with my boyfriend, so I wasn’t climbing with him. I was climbing simply because I had missed it so badly and wanted to feel it again. At that point, I realized that I was climbing because I wanted to. That was a huge turning point for me and my climbing.

With the new crop of young strong girls like the Alex's (Alex Johnson, Alex Puccio), were there frustrating times when you felt like maybe your best was behind you? Ultimately, how did you block out those doubts long enough to send, or more importantly, not to abandon [past project] "The Automator"?

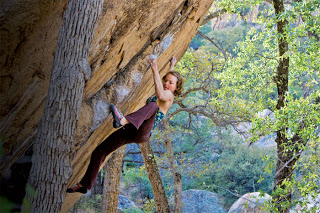

"European Human Being" V12 Photo: Ryan Olson

There were definitely times when I felt like the old talent, and there are still moments when I feel that way. It is becoming more and more typical that I am one of the older competitors at a comp, but I try my hardest to use that as a source of motivation instead of an excuse for failure. There will always be someone younger, stronger, better. But I can’t change those people, I can only try harder to keep up, or better yet, to lead. Even if I can’t be the strongest, I can use my experience to my advantage. I also find it very motivating that I might be able to help progress the sport now, so that stronger and younger climbers might build on my accomplishments and take them further. My generation stands on the shoulders of those female boulderers that came before me, and there would be nothing more satisfying than knowing that a future generation might stand on the shoulders of me and my peers.

As for "The Automator", competition with the 'younger generation' certainly played a part in my doing that boulder. Flannery Shay-Nemirow invited me to try the boulder with her, and although she isn’t too much younger than me, I think she represented the younger and stronger up-and-coming generation in my mind. I climbed on it with her and definitely felt motivated to try harder to keep up. I wouldn’t say that I was trying to do the boulder just out of pure competitive desire, but being pushed by a younger and stronger climber certainly didn’t make my efforts less intense. However, when it came down to actually completing the boulder, I don’t think I would have done it had I been solely focused on the competitive aspect of it. Instead, I focused on how much I wanted to help progress the sport for the future generations, how badly I wanted to leave my teeny tiny mark on my teeny tiny sliver of the sport. And in the end, I just wanted to do it to do it, for myself.

Speaking of competition, you said something interesting in an interview with Pete Ward after the recent ABS Nationals, where you placed 2nd behind Puccio. You mentioned a rivalry between the two of you, then said, “At least I have a rivalry with her, maybe she doesn’t have a rivalry with me.” I was pleasantly surprised to hear that come out of a normally reserved Angie. Particularly, that you could realize that the rivalry is a psychological tool you use, and might not even really exist, (though I think it must, unless she is a Jedi). Do you purposely use these psychological tools or are they just born out of the years of competition?

Beast. Photo: Brendan Mitchell

It’s true that I have a personal rivalry with Pooch, and I strive to beat her someday in a competition because I have a great deal of respect for her as a competitor and would like to reach a level of strength closer to hers. For me, friendly rivalries like this do serve as motivation for me to train harder and try harder in competitions. However, that is sometimes a risky attitude to have, because when you start worrying about the performance of others in a competition, it is often distracting and detrimental in the end. But that is the nature of competitions; the routes are always changing and the only thing that stays relatively consistent is the field of competitors. Some people don’t like competitions for that reason, because they would rather focus on competition with the self instead of with others. But the way I see it, events where me, Pooch, AJ, Francesca, Lizzie, Sasha, etc. are going head-to-head are an amazing source of motivation for all of us and a great way to help raise the bar in our sport. I try hard to keep up with all of those girls and hope that my trying hard pushes them to try harder, and that the cycle inevitably leads to progression. That’s what it’s all about.

Top American climbers seem to have a tough time grasping the concept of being coached, or even following a training schedule. What made you decide that having someone help you with your training was a good idea?

For 14 years, I had some serious weaknesses in my climbing. I always knew that, but it never seemed to be enough of a problem to hold me back drastically. But, over the past 5 or so years, women’s comp boulders have become more dynamic and it has become harder for me to cheerfully ignore my weaknesses if I want to keep up and progress as a climber. So, last year, in preparation for Nationals, I decided to get help with training from a friend who knows my climbing style very well. I knew that it would be easier and more efficient to have someone else sort of force me to do what I was bad at. In addition to providing much-needed structure, my friend’s presence also helped me keep a good attitude and give full effort more often. Because I am basically a shy person, when I am climbing with someone else I tend to censor my negativity and put up a front of sorts to hide any underlying frustration I am feeling. So, having my coach around had the added benefit of keeping my spirits high and my effort closer to 100%. My climbing definitely improved as a result of asking someone else to help me. Now, I often wish I had even more structure for my training. I watch these specials on ESPN about Freddie Roach, coach to Pacquiao, and wish that I had someone to really bust my butt like that guy does. I’m sure it would be a sufferfest, but I’m also sure it would be worth it. Maybe Freddie needs to get into climbing. ;)

Not enough money in it! I’ve always been a big boxing fan, and often reference Angelo Dundee (trainer of Ali and Sugar Ray Leonard) when talking about training. Dundee never boxed a round, but somehow shaped great boxers. Do you believe that other top climbers could benefit from more structured training, even from climbers not as talented as they are? What about if you take formal competition out of the equation? Where does training fit in then?

I have no doubt that there are many top climbers who could benefit from more structured training. After all, the thousands and thousands of pro athletes in other sports who all have trainers are probably not wrong. I am all for the idea that the best training for climbing is climbing, but I am also pretty convinced that certain forms of strength training and conditioning could be incredibly beneficial to one’s climbing. For that type of training, a top climber could be trained by someone not as talented as they are and still benefit greatly. I don’t think I’m the only climber out there who doesn’t enjoy working weaknesses, so in that respect a lot of top climbers could benefit from having more structured training to target those weaknesses.

As far as non-competition training is concerned, I think that structured training can still be beneficial, although I do believe that climbing on real rock is an irreplaceable form of training for sending outside. Personally, I know very little about conditioning and strengthening exercises, so I would definitely trust a trainer to teach me about those things. When it comes to actual climbing, however, I would have to know that a person is an exceptionally good climber, (not necessarily a stronger climber, just a very skilled climber,) before I would take his/her advice regarding climbing seriously.

On another note, during finals at Nationals, on problem #3, you’re the only competitor who all out jumped for the big volume. I KNOW the old Angie would have found some other solution. The last step in learning a new skill is having it mastered to the point of knowing when to pull it out of the bag. If your jump hadn’t worked, it would have been a very easy moment to give up on addressing that weakness. What were your thoughts when you saw the solutions the other girls came up with?

My very first thought was, “Well, that was stupid, Ange. What the hell were you thinking trying such a risky jump???” In reality, I thought AJ had done that method, based on my observation of the crowd’s reactions. I am finding that a new challenge that now exists is that I have this new 'tool' - this jumping thing - that I can do now, and sometimes I get too excited to put it to use, and I forget to just let my body climb like it wants to and jump only when I need to. It’s true that a few years ago, or even a year ago, I never would have tried that jump. But now I am sort of hyperaware of the possibility that jumps might exist, and I’m still over-thinking that part of it. Soon enough, I’m hoping that the pendulum will swing back to a more middle ground, where I learn to jump when I need to and climb like the 'old Ange' when I need to. And as you said, that is when I will have truly mastered jumping. In this particular case, it worked out alright because I pulled it off, but had my method failed, I might still be beating myself up about it…

I'm sure with the "first female to climb V13" tag, comes pressure to do another, or to do V14. Is it a balancing act between the pressure and finding your own joy in climbing, and is there anything you do to help navigate that?

It’s funny, because when I did "The Automator", I remember having that moment that I often have after accomplishing a goal when I think, “Alright, I did it; I’m satisfied; I can stop putting pressure on myself.” Of course, I always know that is a joke, because I will never be completely satisfied, and I will always put pressure on myself to do better. So, yes, there is definitely a certain amount of (predominately) self-imposed pressure to climb another V13 or climb V14. This past summer I struggled with the pressure/joy balance. I decided that before I attempted a V14, it would be a good idea to try another V13. I picked "Freaks of the Industry", another crimpy traverse in the Park that suited my style. I had started working on this problem at the end of the previous season, and I had done all the moves. I was confident that I could finish it this past summer, and that was my first mistake. I started falling at the end of the boulder after about 7 days of effort. I continued to fall at the end for another 18 days before snow ended the season. I was forced to remember that V13 is HARD, and just because I’ve climbed one doesn’t mean I can just hop on another one and get it done.

3 years of efforts. "European Human Being" V12

There were so many days when I was up there alone, cursing the boulder, even crying sometimes because I was so frustrated. It was at those points that I would have to slap myself and look around at where I was. I was alone, in one of the most beautiful places I know of. And no matter how pissed off I was, I would always try to remember that I wouldn’t be in this amazing place without climbing, and that always reminded me how much I wanted to be right there at that moment, flailing on a piece of rock, feeling utterly frustrated yet content. I miss those moments during the winter when I am almost always climbing with other people. I never realize completely when I am trying a project just how much satisfaction and joy I get from the process of it all and the time it often provides me to be alone doing the thing I love.

This reminds me of the conversation you and I had last time I was back in Cincy, when we talked about the risk involved in trying something at your limit instead of going to climb a 'sure thing.'

Exactly. That’s something I’ve struggled with myself over the last couple of seasons. How do you plan on approaching that balance between risk and reward for the upcoming season? The possibility of walking away empty handed… again… is pretty daunting.

Yes, that possibility is very intimidating and I think about it often. Just a few minutes ago, for example, I had to make a list of recent ascents, and my list was pitifully small. Because I spent nearly all of last season climbing on a single boulder, I have nothing to ‘show’ for it, in a way. Of course, I know better than to think that I really walked away ‘empty handed,’ because I took a great deal from the experience. But because I didn’t send, there isn’t that final validation of all of that effort. It is certainly tempting to say that this season I will just go climb things that I know I can finish, and end up with a nice healthy list of sends, and a feeling of validation. But personally, I get much more out of an accomplishment if it involves taking a bigger risk and making a bigger time commitment. Last season, I took that idea to the extreme, and spent nearly every single climbing day at the same boulder. While I don’t in any way regret last season’s efforts, I would definitely change some things about my approach. In the upcoming season, I plan on rationing my motivation more wisely by climbing on some other boulders in between time spent on my project. It’s painful to step away from a boulder when you think that any day you might send, but at some point after falling on the last move for days and days, it’s not a bad idea to give yourself some ‘reward’ on another boulder, to get back in that rhythm of succeeding instead of failing. It’s so easy to ‘learn’ to fall at a certain point on a project after doing just that almost every single attempt. It’s not bad to take some time to reprogram your brain and break that habit. But that’s easier said than done, because when success seems so close, it’s hard to turn your back on it. But in the end, the project isn’t going anywhere, and eventually, whether it be tomorrow or ten years from now, success will come, and it will all feel worth it. On a side note, I often think about what we discussed at some point during one of my recent visits — the thought of what people like Daniel Woods and Paul Robinson and all the other mutant strong guys could accomplish if they spent 30 days trying something. If Woods can climb V15 in fewer than 10 days, what would happen if he took the risk of not sending something for a few months, and put that time into a ridiculous project? I think we would see the next level…even though I can’t even imagine what it would look like. Success is addictive, and when the option to succeed exists, potential failure isn’t very alluring.

The time of her life. Photo: Ben Alexandra

Something tells me that we haven't heard the last of Angie Payne. There's just too much joy in it.

Pressure. No matter if it's a comp, a project, self-inflicted, or external - we all feel it.