Breaking Beta | Sport Climbers vs. Boulderers: Who is Stronger?

In this episode, Kris and Paul discuss a study that dares to touch THE ultimate strength debate climbers love to argue about:

Comparison of Climbing-Specific Strength and Endurance Between Lead and Boulder Climbers

authored by Nicolay Stien, Atle Hole Saeterbakken, Espen Hermans, Vegard Albert Vereide, Elias Olsen, and Vidar Andersen; and published in PLOS ONE in 2019.

They’ll attempt to determine whether or not there’s actually scientific evidence determining if the stronger climbers are those toting crash pads or hauling ropes. Tune in to find out if all that time you’ve spent hanging draws means you’ll never send your bouldering buddies’ warmups, or if all their top outs have done nothing to prepare them for clipping chains.

*Additional studies/resources mentioned in this episode:

Haemodynamic Kinetics and Intermittent Finger Flexor Performance in Rock Climbers authored by Simon Fryer, Lee Stoner, Adam Lucero, Trevor Guy Witter, C. Scarrott, Tabitha Dickson, M. Cole, and Nick Draper; published in the International Journal of Sports Medicine, 2014.

New episodes of Breaking Beta drop on Wednesdays. Make sure you’re subscribed, leave us a review, and share!

And please tell all of your friends who slowly and frustratingly sport climb their way up boulders, maybe even wearing a harness, that you have the perfect podcast for them.

Got a question? Comments? Want to suggest a paper to be discussed? Click below and let us know!

Breaking Beta is brought to you by Power Company Climbing and Crux Conditioning, and is a proud member of the Plug Tone Audio Collective. Find full episode transcripts, citations, and more at our website.

FULL EPISODE TRANSCRIPT:

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 00:05

You're a fine chemist, really, with a promising future. It's just that I....that we, just have different rhythms, Gale. It's, it's as if I'm classical, but you are more jazz.

Jazz.

Jazz. Yes. And God knows there is nothing wrong with jazz. It's simply that I require classical.

Exactly.

Kris Hampton 00:48

Maybe I'm getting the metaphor a little backwards here, but there's nothing wrong with sport climbing. I just require bouldering. Hahaha. That seemed like the appropriate one for today. How are you?

Paul Corsaro 01:05

Doing pretty good. Starting Monday off here in Chattanooga. Had a good weekend of sport climbing and bouldering. Yeah, kinda did a little bit of both.

Kris Hampton 01:12

Which did you feel like you were being stronger at?

Paul Corsaro 01:18

Um.......

Kris Hampton 01:18

Hahaha I don't know if it's a question that's answerable.

Paul Corsaro 01:21

Haha Yes.

Kris Hampton 01:24

Exactly. Yes. All right. You know, when I when I was first reading this paper that we're going to talk about today, I liked to sort of imagine that the authors saw it as a climbing version of West Side Story with like, lead climbers as the Jets and boulderers as the Sharks and they're like all singing, battling against each other in their tests.

Paul Corsaro 01:56

Instead of walking towards each other snapping, they're just blowing chalk off their hands.

Kris Hampton 02:01

Hahaha. Exactly. The French blow battle. Yeah, absolutely. All right. The paper we are here to talk about today is called "Comparison of Climbing Specific Strength and Endurance Between Lead and Boulder Climbers". Authors are Nicolay Stien. I'm going to mess some of these names up horribly.. Atle Hole Saeterbakken, Espen Hermans, Vegard Albert Vereide, Elias Olsen and Vidar Andersen, really, I should just say Nicolay Stien et al, but you know, I'm trying here. It's it's a call back from my youth divisionals MC days where I wanted to say everybody's name.

Paul Corsaro 02:50

It was a valiant effort, I'd say.

Kris Hampton 02:51

Haha. It's in... it's in the journal "PLoS One" 2019. And the purpose here was to examine the maximal and explosive strength in dynamic and isometric pull up to identify the utilization rate of force using a ledge hold compared to a jug hold and to compare forearm muscle endurance between lead and boulder climbers. Just a quick note here, they say "ledge" throughout this. It's what climbers call an edge. They are using a 23 millimeter edge, I believe. So some of us are like, "Ledge? That's a jug too.", so just just to clarify there. Any anything when you were going into this paper, like before you picked it up and read it, that you thought?

Paul Corsaro 03:45

Um, I was really interested interested to see what was gonna come out of it. You know, we always hear certain assumptions about different disciplines of sport on.... different disciplines of our sport on who's gonna be stronger on certain moves, or who's gonna be more powerful, so on and so forth. So this looks like a good kind of look at that and see in and would highlight if that's actually the case, or if it would give us a direction to go to look at this little deeper, but I thought it was a good, good goal, a good purpose of a study to kind of start figuring things out. It could be useful as a coach when you're looking at how am I going to program for an athlete depending on their goals, so I was excited to dig in.

Kris Hampton 04:27

Yeah, totally same for me. Let's jump into this thing and see what became of it.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 04:34

You clearly don't know who you're talking to, so let me clue you in.

Paul Corsaro 04:39

I'm Paul Corsaro.

Kris Hampton 04:40

I'm Kris Hampton.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 04:41

Lucky two guys, but just guys, okay?

Paul Corsaro 04:45

And you're listening to Breaking Beta,

Kris Hampton 04:48

Where we explore and explain the science of climbing.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 04:51

With our skills, you'll earn more than you ever would on your own.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 04:56

We've got work to do. Are you ready?

Paul Corsaro 04:59

I'm ready, are you?

Kris Hampton 05:02

I think I am. I drove, like 12 hours yesterday, and I'm operating on much less sleep than I would like to, but I think I think that I'm ready, so let's jump into the methods.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 05:20

In a scenario like this, I don't suppose it is bad form to just flip a coin.

Paul Corsaro 05:27

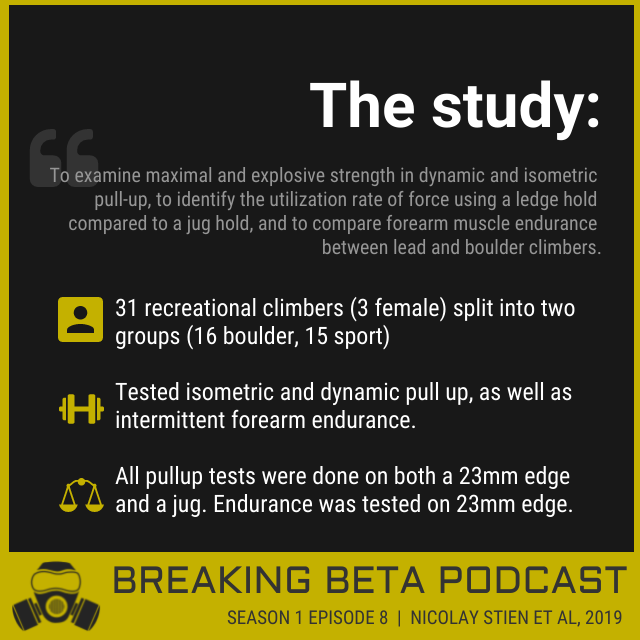

Alrighty, so this was a cross sectional study, first off. So a cross sectional study is a study that looks at data from a population at a specific time. So just we got to keep all this in mind, as we're looking at these results as they come come out. There were 31 subjects, twenty....twenty-eight male, three female. They were split into two different groups, bouldering group and a sport climbing group and this is just based on their self reported discipline they did the most. So they said, "Yeah, I'm doing more bouldering", "I do more sport climbing" and they split them into those groups. There were 16 in the bouldering group, 15 in the sport climbing group. They looked at some just descriptive data about these groups and I think ones that were meaningful here was the bouldering group had about close to six years of experience climbing.These are all the the means, so there's going to be some variation there obviously. Sport climbing group was around nine. Both of them trained about a little over three and a half times a week. I think we had 3.9 for the bouldering group, 3.4 for the sport climbing group. And their self-reported redpoint grade for the bouldering group was 11d or 12aish and the sport climbing group was in between 12c and 12d. So I think those are all useful to show, you know, where we're at, coming from a climbing ability level here. And you know people who have been climbing for close to six years at a minimum it looks like, if you just look at the mean, so people who have been climbing for a good amount here.

Kris Hampton 06:53

Did you, did you pull up the chart, the IRCRA chart?

Paul Corsaro 06:57

Yeah, I did. I did. I have that bookmarked now, because I'm seeing more and more of that in these recent more later papers, so it's good thing to have.

Kris Hampton 07:05

Yeah, I think it's great. In fact, I'm going to, I'm going to point Dale toward it and see if we can see if we can use it in any way with all of our data.

Paul Corsaro 07:14

I'm sure he can configure something out. Yeah, so they got all these a descriptive data about the groups and then they moved on to the testing. So did a light warm up before all these testings. They did four different measures that we're going to explore here. First measure was a maximal isometric pull up. So they did these on both the jug and the ledge, which is that 23 millimeter edge, that you get set up about 90 degrees of elbow flexion and with a harness, you're attached to a force scale. So there's a lot of these out these days. One of those where you pull as hard as you can for five seconds, and they get...they're looking at the max force, your average force, the average rate of force development for both the jug and the edge. They also looked at an explosive dynamic pull up, which is just from a dead hang, pull as fast and as hard as you can. They had a device on the harness that sampled I think it was 11 milliseconds or 10 milliseconds, something like that. But they were able to see how fast you did your pull up when you were doing that movement.

Kris Hampton 08:21

I thought the setup for this was nice. Just because we've been recently seeing so much of like, locking the body down and, and pulling, as opposed to being able to try to pull the body up, if that makes sense, like sitting and being locked down. And what they did was they basically attached the climber to the floor, but they were suspended, so the climber was hanging and then they were attached to the floor with a static rope through that load cell, which I thought made a little more sense. It's a little more specific to how we pull while we're climbing.

Paul Corsaro 09:08

And it's interesting too, because then they did do, for the last test, the forearm muscle endurance test, they went back and did do the seated version, where they were seated, had a padded barbell in front of their chest and behind the behind the arms to make sure they weren't moving in the shoulders or back. And what they did is they had a custom build edge that was also 23 millimeters deep, attached to that same force cell and using 60% of their maximal isometric force, which I thought was cool how they kind of tied it to that first test, you they would pull as hard as they could or they'd pull at least 60% of that max force for seven seconds, and then rest for three seconds. So they basically kept doing that until they couldn't produce that 60% force, so that was when they had the fatigue cut off and the measurement they took there was just the total time of work. So we've seeing similar things of this in climbing assessments where it's a repeater to failure or repeater until you can't hit a threshold, so it was cool to see this in a study as well.

Kris Hampton 10:11

Do they make it clear in there...I hadn't really thought about this until you just said it. It would be interesting to be able to see all of the data here. Do they make it clear whether any of the climbers did pull as hard as they could on those intermittent tests or did they all try to keep it just above 60, like regulating their effort level for each attempt?

Paul Corsaro 10:37

I think they just had to hit the threshold. So they had a little screen in front of them where they could see immediate feedback, but I don't see if they had any instruction on whether it was to pull as hard as you could or just be above the threshold.

Kris Hampton 10:52

Yeah, I didn't I don't remember seeing any in there. I'd be curious, because you could, you could be very tactical with that test,

Paul Corsaro 11:00

100%

Kris Hampton 11:01

You know, hitting 61% and just holding that level, as opposed to going 85% for the first bunch of reps or whatever.

Paul Corsaro 11:10

Yeah, so they did all these, they did these four tests. It was a standard order. I had it here somewhere... yeah, the standard order...so they did the isometric pull up on a ledge or edge first, then they did..... so the 90 degree pull. Then they did the 90 degree pull on the jug edge. Then they did that dynamic speed pull up, and they finished with the intermittent test. So they had three to five minutes rest in between each test condition. They had three trials, I believe, for every test with a minute rest in between and took the highest of those three trials. And they instructed the subjects to refrain from climbing and climbing-related training for 48 hours before testing, so people were coming in fairly fresh. They did a good job standardizing things for everybody and then they got these results and examined the data.

Kris Hampton 12:01

Yeah, and I think they...their hypothesis going into this is similar to what most of us would hypothesize, that the boulders would demonstrate greater maximal force, greater rate of force development and pull up velocity, while lead climbers would demonstrate greater climbing-specific forearm muscle endurance. And they expected that both groups would see reduced force output and rate of force development using the edge as opposed to the jug, which makes total sense to me. I do think it was... I think it was very smart that they did the 60% of max and then when it dropped below 60, the test was over. And I suppose that they were really trying to isolate the finger flexors and the forearms there, so that's why they did it seated, as opposed to letting the shoulder get involved or any of that, with the hangs.

Paul Corsaro 13:04

I think a cool thing they did with that 60% threshold cut off was there was less mental or subjective signals to stop. You know, if someone's a sport climber, and they're used to pushing through a pump a little more, if they went to maybe a volitional fatigue, I could see that maybe being that mental aspect being a confounding element of all this. So I think that was a good idea to have that threshold, just to keep everybody honest and keep it just objective and numbers.

Kris Hampton 13:33

Yeah, yeah, I think it I think it's set up pretty smart. And let's take a quick break, and we'll be back with the results and our verdict.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 13:41

Please. Alright, I really need a break here, okay.

Lana Stigura 13:47

You're listening to the super nerdy podcast, so I can only assume that you're interested in improving your climbing. Well, good news, you're in luck.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 13:54

Yeah science!

Lana Stigura 13:55

We have training options for nearly every level climber in nearly every situation, from general prep to fully custom, from ebooks to weekly plans delivered via mobile app. Visit Powercompanyclimbing.com/breakingbeta for more info. And while you're there, check out Kettlebells For Climbers 2, now available as either an ebook or a Proven Plan, the follow up to our wildly popular Kettlebells For Climbers plan, that started so many climbers down the path to being stronger, better prepared and more athletic.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 14:22

Let's all get back to work for Christ's sake, okay.

Kris Hampton 14:25

All right, we have returned from our break. And let's take a look at the results of this paper trying to decide who is stronger, boulderers or sport climbers?

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 14:38

Whatever you think is supposed to happen, I'm telling you the exact reverse opposite of that is going to happen.

Kris Hampton 14:47

Okay, I think I think as expected, for most of us anyway, what what this paper saw is that boulderers are the supreme athlete.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 14:59

I am the one who knocks!

Kris Hampton 15:02

Essentially. So boulderers were stronger and more powerful pretty much across the board. All of the the force measurements they got, using both the 23 millimeter edge and the jug, boulderers showed higher force.

Paul Corsaro 15:20

And that was both raw numbers and when they scaled it for bodyweight, too. So those significant differences remained, so I think it just makes that an even stronger point to come out of all this.

Kris Hampton 15:34

I like that the Sharks are winning here. Both groups, as one would expect, showed lower peak force, average force and rate of force development on the edge versus the jug. So meaning we could pull harder on the jug than we could on the edge. As climbers, that makes total sense to us. One interesting thing about that, though, I thought, was that it was essentially the same drop for all of the groups.

Kris Hampton 16:04

So moving from the jug to the ledge it dropped by...you know... essentially, they showed about 57 to 69% of their max force, on that 23 millimeter edge.

Paul Corsaro 16:04

Yeah.

Paul Corsaro 16:17

Yeah

Kris Hampton 16:18

Makes me curious if there's some sort of a formula you could come up with, for as a hold goes down in size, how much force is going to drop. I wonder if there is a somewhat linear relationship there?

Paul Corsaro 16:34

Yeah, that could be an interesting thing to explore. And I think you could also get some good coaching kind of heuristics out of that too, where say, you only have a jug to test with for some reason, and you need to guess you know, okay, so we're gonna use this and build a plan off of a larger, you know, mid 20, mid 20 to 30 millimeter edge. Maybe you can use some of these ratios or proportions to at least have a starting spot, if you don't have anything else to work with.

Kris Hampton 17:03

Right. Totally.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 17:04

Yeah science!

Kris Hampton 17:07

The most interesting thing to come out of it, I think, is that in the intermittent endurance test, the repeaters, the time to fatigue between the two groups, boulderers and sport climbers showed no difference.

Paul Corsaro 17:21

And that's the surprising one, right? You'd think the sport climbers would be better at that, but they weren't.

Kris Hampton 17:28

Yeah. Let's discuss a little bit why that might be. Number one, I think we have to look at the 60% of max. In my view anyway, particularly, since bouldering gyms are taller and taller nowadays, I think that the big difference between a sport climber and a boulder is more about their aerobic endurance, how long they can, they can do really sub maximal effort. So maybe testing at a lower percentage, you know, 40%, or something like that, would just discern a little more.

Paul Corsaro 18:16

They actually talk about that in the discussion as well. So they say in the test they performed in this study, the average time of this intermittent test is about 107 seconds for the sport climbers, and then 83 seconds for the boulderers. And they said, you know, climbing a boulder route is around 30 seconds, give or take, there and a sport climbing route anywhere from two to seven minutes, so maybe they weren't getting into that time where they're going to start seeing the differences. And they used a, Fryer et al, used a similar test of a 10:3 repeater using 40% of that maximal force, and it led to a bit longer duration of that test. So I think you're kind of right on the money there with that thought.

Kris Hampton 19:03

Yeah, also, this is one of the misleading things about statistics, is that while while it may not be statistically significant, 107 seconds versus 83 seconds could very much be the difference between sending a sport route and not sending a sport route.

Paul Corsaro 19:22

Very much so.

Kris Hampton 19:23

So you know, there there is a difference there, even though in the abstract it says showed no difference, there is a twenty....what is that....twenty-four second difference.

Paul Corsaro 19:36

Yep. I mean,

Kris Hampton 19:37

Which seems fairly large to me.

Paul Corsaro 19:40

Yeah. I wonder we could look at that table and maybe recruit Dale to run some statistics and explain some of that.

Kris Hampton 19:47

Yeah, exactly.

Paul Corsaro 19:49

Um, another thing I thought too is I would be interested to see actually if they increased the threshold to see if that created a separation too. You know, harder sport routes have harder boulders on them, so being able to do harder contractions or harder efforts, maybe they'll have more capacity for that. I think maybe either raising or lowering and just seeing what happens would be interesting ways to take this.

Kris Hampton 20:12

Yeah, totally. Also a thing that sort of jumped out at me, and I couldn't really quite understand.... I've like done these gymnastics in my head a few times. They didn't gather the bouldering grade for the boulderers and it seems like to me, it would have made a better comparison if they took that IRCRA chart, the International Rock Climbing Research Association chart, and said this sport grade lines up with this bouldering grade, so let's compare the forearm endurance of those two groups, as opposed to let's gather the sport climbing grade of boulderers and compare that 1:1 with sport climbers.

Paul Corsaro 21:05

Yeah, it just seems like another piece of information that could be really helpful and illustrate a lot of things they just didn't get, especially when they're considering boulderers versus sport climbers, and then not even really looking at...

Kris Hampton 21:20

At their bouldering grade.

Paul Corsaro 21:20

Yeah, so that that was odd to me. I have that highlighted in red as well, I was gonna bring that up.

Kris Hampton 21:24

I mean, they could very easily have been...so the bouldering group came in at around an average of 11d/12a. If you're if you self identify as a boulderer, it's entirely possible that you've only climbed 11d/12a because you've only been sport climbing a few times in the last year.

Paul Corsaro 21:43

Yeah, you could boulder V10 and have climbed 12a.

Kris Hampton 21:45

Right, exactly.

Paul Corsaro 21:46

I've seen that plenty of times.

Kris Hampton 21:48

Absolutely. So that that throws it way off for me. Anything else in here that looked particularly good or particularly interesting to you? Another thing about the boulderers and sport climbers.... I think that if we, if we took..... because they took the like mental side of it out, that also is going to make the number a little more equal. I think one of the one of the big components of sport climbing, that you can't test for a test like this, so you know, no, no shots at all to the researchers, is the the mental component of it. How much can you relax when you're up above a bolt versus how hard you're trying?

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 22:43

That's pathetic. How hard did you even try or did you?

Kris Hampton 22:51

And, and we can't, you know, we can't strip that away from sport climbing, but we can strip it away in this endurance test. So it's entirely possible that the endurance just does get much closer, like it shows up here, when we take all of that fear component, all of that mental component out of it.

Paul Corsaro 23:10

Yep. I think another interesting thing was that the rate of force development was one of the most marked difference between the two. So I think it does highlight the importance of having some way to measure that or assess for that in your own climbing or of someone you're working with, because I think that could highlight potential for improvement, especially if you're trying to move back and forth between disciplines, things like that.

Kris Hampton 23:34

Yep. They they mentioned in here, and I think this is an interesting, interesting discussion to have, is the kind of the "Which came first, the chicken or the egg?" argument. You know, did these people, when they decided to boulder more, did that increase these aspects of their climbing or did they self select for bouldering because they were better at those aspects of climbing. They were they were stronger, more powerful, so they became boulderers, or they had better endurance so they became sport climbers. I think that's an interesting discussion. What do you suspect is the case there?

Paul Corsaro 24:14

I think it might be both. I think it really highlights how useful something like limit bouldering can be in your climbing overall, because that's going to be something you can use to increase all of these metrics, without having to really dig into a whole lot of non climbing training, if you will. So I think just the act of bouldering probably had a big importance in improving on a lot of these tests.

Kris Hampton 24:41

Yeah, and I suspect that like 20 years ago, in climbing gyms, the difference may not have been so so marked, because the boulders looked like sport climbs. Nowadays, with bouldering becoming more and more powerful, more and more gymnastic, I think climbing on boulders in the gym will very often increase your, your rate of force development. It'll make you more powerful over time. So, so I agree, I think it's probably a little of both. You know, part partly I enjoy being more powerful and doing these gymnastic moves, so I'm going to spend more time doing it, so I'm going to get better at it.

Paul Corsaro 25:29

Yeah, I agree with you on that.

Kris Hampton 25:33

What does this paper not say?

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 25:35

What is close? There's no close in science, Barry. There are right answers and wrong answers.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 25:42

Yeah, but I'm just saying, Mr. White.

Kris Hampton 25:45

I think I think the number one thing, frankly, that it does not say, even though it does say it in the abstract, this is another another strike against the abstracts, is that boulderers have the same endurance of sport climbers. I don't think it actually says that.

Paul Corsaro 26:05

Yeah, I was gonna say that it could be easy to take this paper as an excuse to not train endurance ever as a sport climber, and just try and train on the strength, but I think that would be an misinterpretation of these results. Even for a cross sectional study, one of the caveats for one of those is that's just descriptive, so it, it doesn't provide any causal links or anything like that. So it's literally just looking at a data set and....or looking at a group and this is what is going on with this group. It's just descriptive. That's it. So it's a piece of the puzzle, but you'll probably need more to make any claims or make major changes in how you go about things.

Kris Hampton 26:45

Yeah.

Paul Corsaro 26:45

Foundational, more than anything else, I'd say.

Kris Hampton 26:48

Absolutely. It also does not say even though I fully believe this to be the case, that all boulderers are stronger than all sport climbers,

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 26:58

I am the one who knocks!

Kris Hampton 27:01

We know what team I'm on at this point. Haha. I switch teams like it just doesn't even matter,

Paul Corsaro 27:08

Haha back and forth.

Kris Hampton 27:09

Hahaha. And I think it also doesn't say that bouldering automatically makes you stronger. I mean, I think that's a, it could be really easily taken away that it says that, but it just doesn't. And frankly, from my like subjective experience, that's something I believed years ago, but then I would go and I would essentially sport climb the boulders, you know. So bouldering really wasn't giving me the added strength and power that it might sound like it does when you read this paper. Let's look at the application.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 27:48

All these little pieces are all part of the story, right? But they don't mean much on their own. But when you start telling me what you know, we start filling in the gaps. I'll have them unlock them before the sun goes down.

Paul Corsaro 27:59

Yeah, I agree. I think when I look at the paper, what I really get from it, as you know, I work as a coach full time.... I'm dealing with people both in person and remote and I think it's really useful to have simple and repeatable tests that you can use to test retest to make sure things are moving up. I think these are all pretty good starting points. I think they can be repeatable. They don't, you know, they use probably some expensive scales and stuff in this study, but you can find affordable replacements for some of this equipment. I think this would be a good starting point if you're looking to build some sort of testing battery. I think you could pull a little bit from these procedures here to use that.

Kris Hampton 27:59

For me, I think I think what I am taking away from this and how I will apply this moving forward, is is really just looking at not all climbing is created equal. So if you're a boulderer versus a sport climber, there might be some slightly different metrics we want to shoot for. You know, I'm not I'm not saying that in terms of, you have to reach this metric to be a boulderer. I'm saying more like, I want to see a little more strength, a little more power as a boulderer than I do as a sport climber and if... and this is something we should talk about as a team, if there were an easy way to measure rate of force development coming up in the future, that would be a great metric to add to the panel that we already gather from climbers.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 29:43

Yeah, science!

Kris Hampton 29:45

Yeah, I like that a lot. They make a few suggestions in the practical application section that I actually sort of as a coach disagree with, at least half disagree with. They do say finger flexor strength training can likely benefit climbers of both disciplines and resistance training focusing on maximal and explosive strength of both the finger flexors and the prime movers can likely benefit both groups and I agree with that completely. We all should be training those things. But then they also.... they go on to say that those things might prove more beneficial for boulderers than lead climbers and I don't know where they came up with the idea that training strength and power is going to be better for boulderers than sport climbers. They also say lead climbers might benefit more from focusing their training on other properties, such as forearm muscle endurance,

Paul Corsaro 30:43

But they didn't even find any difference in the studies. That's interesting where that came from.

Kris Hampton 30:47

Right. That That confused me quite a bit. I wasn't really sure how they came up with that unless it's just the they were working off of their original hypothesis when they made this suggestion. So I think that's ,I mean, that's a common sense suggestion, but I don't think this paper bears out that suggestion.

Paul Corsaro 31:14

Yeah, I agree with you.

Kris Hampton 31:18

Anything else you're taken away from it?

Paul Corsaro 31:20

Um, I've definitely been thinking, and I talked about it a little bit earlier, I've definitely been thinking about that...the relative force utilization, pretty much the drop in force production from the jug to the edge.

Kris Hampton 31:33

Oh yeah.

Paul Corsaro 31:33

I think that'd be an interesting thing to dig deeper into, see if there's A, more research out there for that, or hey, maybe just start playing with it in the gyms. We're lucky enough to have a force scale that we can use, and maybe just see if we can replicate or start figuring some things out there, because anything we can do to make things simpler and more approachable and repeatable and less time costly, I think, would be a good thing to explore.

Kris Hampton 32:00

Yeah, I do, too. Overall, I think it's a it's a well done paper. I think that I think that it's, you know, a useful thing to look at. It sort of validates the the common sense that we all, we all already believed about the properties of bouldering versus sport climbing, minus the endurance part. I think there is, I think they showed a difference, but statistically, they couldn't say, "Oh, here's this difference" and I think that's one of the failings of statistics.

Paul Corsaro 32:37

Yep. And I, I know there's a lot of papers nowadays, relatively, that are looking at that intermittent hang, or pull or what have you. It'd be interesting to just look at all those and find a way to maybe combine them all and see if we can get a little bit more clear outcome from those.

Kris Hampton 32:56

Yeah. Yeah, for sure. And something we've mentioned a few times throughout this season, which is coming close to an end here, is that I think it's great that science works this way. Like this is a an interesting, start to the conversation of that and let's take it a bunch of different directions and see where it leads and see what we find. So, so for me, this one was a good one.

Paul Corsaro 33:23

Likewise, right there with you.

Kris Hampton 33:25

Alright, you can find both Paul and I all over the internets by following the links right there in your show notes. And you can find Paul at his gym Crux Conditioning in Chattanooga, Tennessee. If you have questions, comments or other papers that you'd like for us to take a look at, hit us up at community.powercompanyclimbing.com. Don't forget to subscribe to the show. Hit the Follow button right there on Spotify and leave us a review. I'm told that it helps. And please tell all of your friends who slowly and frustratingly sport climb their way up boulders, maybe even wearing a harness, that you have the perfect podcast for them. We'll see you next week when we discuss creatine supplementation and whether or not it can benefit you as a climber.

Paul Corsaro 34:10

Catch you on the flipside.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 34:12

It's done.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 34:13

You keep saying that and it's bullshit every time. Always. You know what? I'm done. Okay, you and I, we're done.

Kris Hampton 34:24

Breaking Beta is brought to you by Power Company Climbing and Crux Conditioning, and is a proud member of the Plug Tone Audio Collective. For transcripts, citations, and more, visit powercompanyclimbing.com/breakingbeta.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 34:38

Let's not get lost in the who what and whens. The point is we did our due diligence.

Kris Hampton 34:44

Our music, including our theme song "Tumbleweed", is from legendary South Dakota band Rifflord.

Breaking Bad Audio Clip 34:50

This is it. This is how it ends.

Explaining the science and calling out the misinterpretations.