The Biggest Red Flag of 2019/2022

** I originally wrote this in early 2020. Before I could put it out, the Covid-19 pandemic began. With that happening, an entire post about spending more time around other people felt a little ridiculous. Two and a half years later, this finally feels relevant again. **

At the start of 2019, I wrote The Biggest Red Flag of 2018. If you haven’t read that yet, check it out. It remains one of the biggest issues I see getting in the way of people’s progress in climbing.

2019’s red flag runs in the same vein of staying comfortable, but in a different way.

Of all of the people that I spoke with this year who were stuck in plateaus, many of them had the same thing in common. They climbed and trained alone.

It’s one thing to be a big fish in a little pond, but some people are more like carnival goldfish living in their own worlds. Don’t be the goldfish.

I strongly believe that, for most people, a good climbing partner is worth more than a great coach. A good partner is someone who is just as invested in your success as you are, and can help keep you honest when things get tough. The only person who might know your climbing better than you do is your partner.

When someone tells me they have plateaued, one of the first questions I ask is, “Who do you regularly climb and train with?” The answer is often the same. It’s either “I climb by myself,” or “I climb with my significant other or some friends, but they all climb drastically different grades than me.” This should be seen as a huge red flag.

One of the easiest ways to improve the quality of your sessions is to climb with people who are around a similar ability level as you, but with a different skillset. Maybe they are a different size or have different strengths. It could be that they find beta better than you or are better at trying hard and executing when the time comes to give send go’s. Sharing the experience of problem solving and pushing to become a stronger and better climber with someone else is one of the best things you can do for your long-term development.

The climbers who get stuck the deepest in this self-imposed rut of climbing alone tend to also be the most dependent on using physical training to solve their progression problems. This can provide a short or even medium-term fix, but often leads to the same roadblock just at a slightly higher grade.

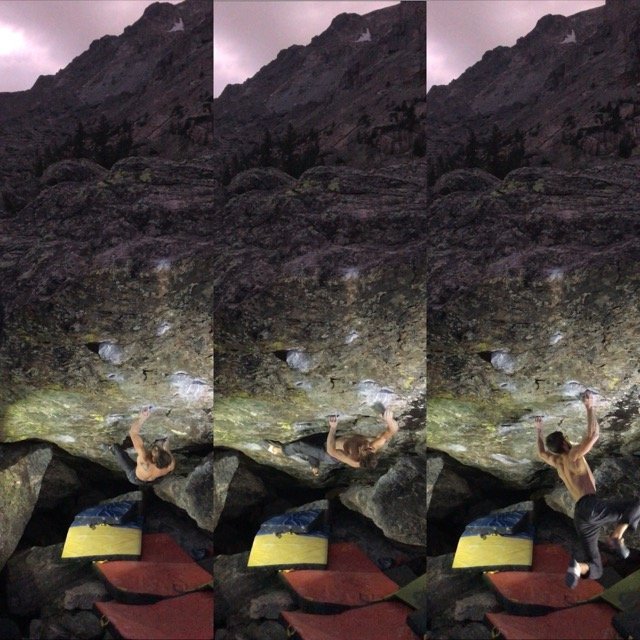

What it looks like when people climb in the gym around each other but not with each other.

To be fair, there are people out there who excel at pushing their limits while climbing and training alone. They are capable of identifying and working on their weaknesses, questioning their own assumptions, and holding themselves accountable when things get hard. These people are few and far between though. While these are skills that can and should be developed, it’s almost impossible to replace the value of a good climbing and training partner.

“If you’re training yourself, you’ll tend to know everything you decide to do. You’ll always push yourself exactly as hard as you feel like pushing yourself. You won’t have any gaps in your training because you have no idea what you’re lacking. Finally, you’ll be able to progress and regress easily in your system since your single follower — you — will know what you want, even if it isn’t something you need to do. I hope I painted a picture of mediocrity here.”

The beauty of climbing is that we don’t have to do this alone. It’s a lot more fun with friends, too.

If this sounds like something you’re guilty of and you want to improve at climbing, then start connecting with people in the gym or out at the crag. You don’t have to become best friends with every person you meet. If there are people you see at the gym regularly who are climbing on the same problems as you, start climbing around them and see if they are someone you climb well with. It’s one of the easiest things you can do to both climb harder and make climbing more enjoyable.

Inspiration is intoxicating, but often fades as quickly as it shows up.