For Those Who Refuse To Work The Moves... Do You Know Where Your Limits Lie?

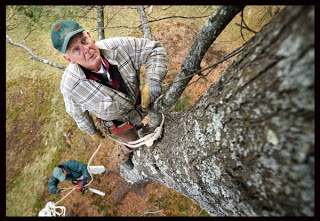

Working the moves on "Ghost Dance" 13c

I used to be one of you. For the large part of my climbing life, I’ve been an onsighter, believing that working a route was somehow a lesser pursuit. Several times I tried to put in multiple burns on a route, but I rarely got further than 5 or 6 attempts, and I never found the joy in the process.

For quite some time, my hardest sends were my hardest onsights. Even a few years into my discovery of sport climbing, the best onsights on my ticklist were only a letter grade or two behind my most difficult sends.

Even those of us who are always in the midst of a long project at home tend to switch to onsight mode while on a trip to a new area. The lure of doing as many new pitches as possible at an accessible grade is terribly hard to combat, especially when there is a deadline looming over any projects you might take on. None of us wants to leave an area having spent nearly all of our time on the same route, do we?

Frankly, I do. Its only in the last 2 years or so that I’ve learned to really love redpointing. There is still something so satisfying about doing a hard route first try with no prior knowledge, testing all of your skills on the fly, requiring you to pull tricks out of your bag at a moments notice. However, there is something about redpointing that goes much deeper. The intimacy with the holds and movements, finding subtle nuances of body positioning that allow the efficiency to tip in your favor.

The first hard move. Believing.

At a new area, far from home, and attempting a climb near your limit, these nuances are amplified. When you aren’t climbing in your comfort zone, digging deeper into the process is imperative. It requires a little more dedication, a touch extra vision, and a heaping helping of what B.J. Tilden said to me when I vocalized how hard a move felt on link: “You just have to believe.”

One of the most remarkable things about redpoint projects, whether at home or on the road, is that they can, and will, continue to prove you wrong.

“If I just stick that move, it’s over.”

Next thing you know, you’re 3 moves above “that move”, and falling off.

“I’ve got that section totally dialed; it’s all down to the final crux now.”

On your next attempt you discover that dropping your pinky from the hold helps you turn into the drop knee a little more, and increases your reach just enough to make the crux move a fraction more efficient.

It’s endless. Yesterday I nearly sent. I was past the crux, on what I think is the last move hard enough that I could fall from. Of course, the top is delicate, and threatens to spit me off every go, but it’s preceded by a no-hands rest where I can get my forearms and mind back into form. I started the route far more fatigued than I would like to be, but I believed. I went to battle, fighting for every inch, only to fail a move away from a rest. I wasn’t disappointed. I was elated.

Making the crux move.

My girlfriend likes to tell the story that when she lowers me off a near send, after just snatching defeat from the jaws of victory, at which point she would be wrought with frustration, the smile on my face is impossible to erase. I love being told who’s boss. Every time a move unexpectedly spits me off, or a section is harder on link than I figured, it’s an invitation to learn a thing or two. These are the times when we can get stronger mentally.

No matter how you slice it, when you complete an onsight, or when you battle your way to a redpoint, you have to know that you can climb harder. There are almost certainly hundreds of missed opportunities to make those moves more efficient. Each one of those new tricks can get tucked into your bag and become part of a new, stronger, smarter you. Even when you lower off after an absolutely perfect rehearsed ascent, there is the feeling that it was too easy... that even though this took more attempts than you've ever taken, you CAN climb harder.

Mid crux. Belief in high gear.

I'm looking for my limit. I can't find it without exploring every possible advantage I can get. All those years of onsighting made me better at quick decisions on the fly. They demanded that I have an abundance of endurance and technical skills at my fingertips. I'm thankful for them. What they didn't require is that I delve deep into the minutiae of seemingly simple movements. I never had to use a grip that I could just barely hold after dozens upon dozens of attempts. If I couldn't do a move, I'd just abandon the climb, rather than sacrifice the time to learn how to do it.

Redpointing routes near my current limit on the road forces me to examine what I've learned, and allow it to evolve within a new style, a new rock, and new movements. The subtleties become ever more important. And maybe most important of all, doing your hardest routes in an unfamiliar setting requires that you believe at a level far higher than your comfort zone requires of you.

All Photos by Becca Skinner.

How can we make better use of our working goes in order to send hard things faster?